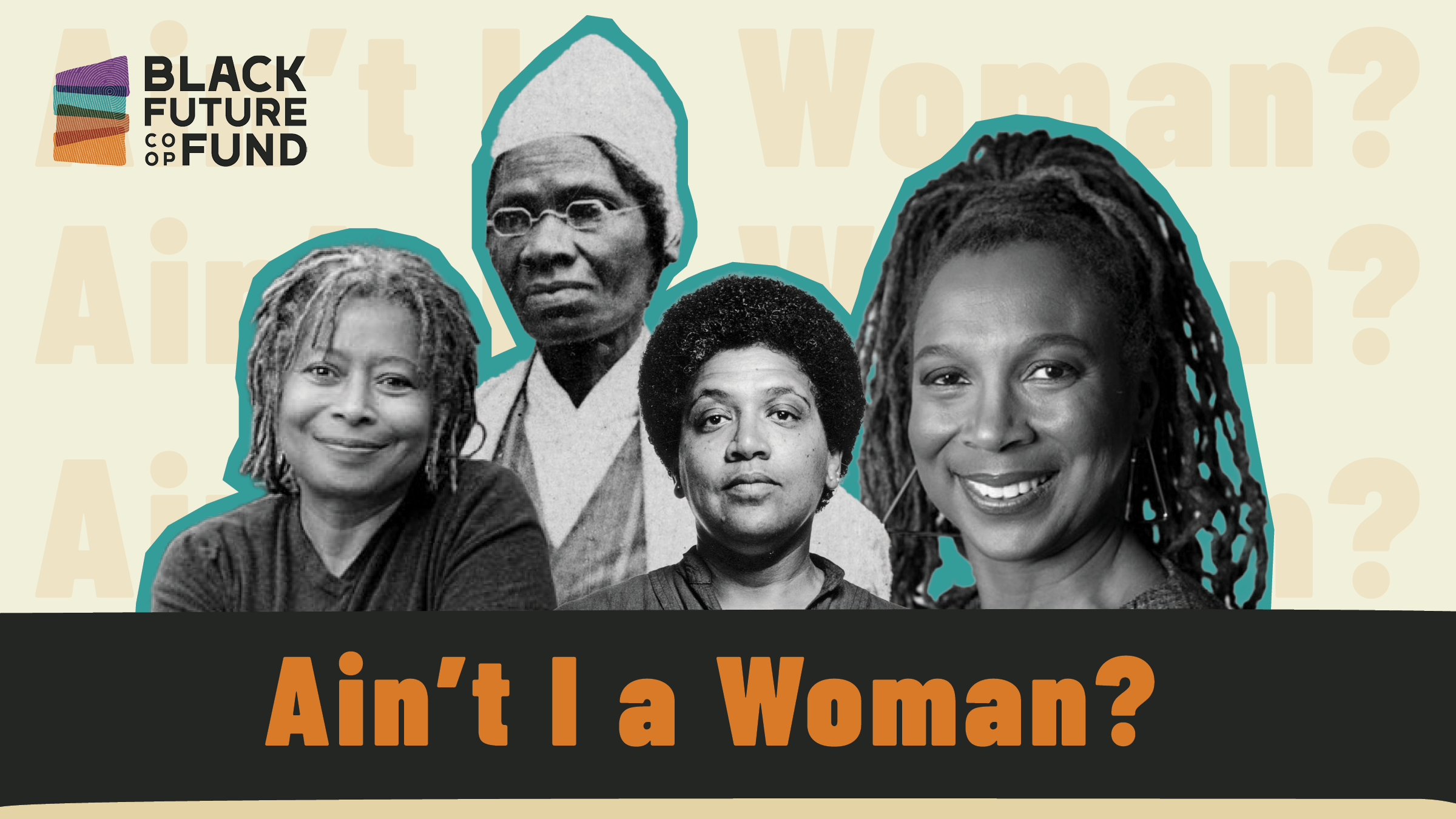

Ain’t I a Woman?: Blackness and Expansive Notions of Femininity

Alice Walker, Sojourner Truth, Audre Lorde and Kimberle Crenshaw

“Ain’t I a woman? Look at me, I have plowed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me. And ain’t I a woman?” – Sojourner Truth

The complexity of Black women’s experiences and perspectives have consistently challenged Western notions of femininity. At the intersections of race, gender, and class, the very existence of Black women pushes against narrow definitions of what it means to be women.

Historically, in the Western imagination, Black women have been either masculinized beasts of burden, desexualized mammys, or hypersexualized jezebels. These seemingly contradictory stereotypes work together in denying and perverting the humanity of Black women, and seek to cast Black women as perpetual others whose value lies in their labor or sexual availability.

Colonizers also actively worked to suppress African understandings of gender fluidity and expansive notions of sexual orientation, further alienating Black women from their full personhood.

Despite a society committed to erasure, Black women have always resisted. In 1851, at the Women’s Convention in Akron, Ohio, Sojourner Truth delivered her famous “Ain’t I a Woman” speech, directly confronting how the nascent feminist movement was attempting to leave Black women behind. White women had historically been promoted as the feminine ideal, requiring protection and delicacy, both of which were categorically denied to Black women. And yet, Sojourner challenged, “Ain’t I a Woman?”

“Womanism is embracing the courage, audacity, and self-assured demeanor of Black women, alongside their love for other women, themselves, and all of humanity.” – Alice Walker

As mainstream feminism developed, and the right to vote led to conversations around the right to work, Black women found their issues sidelined yet again. After all, the American economy had always relied upon Black women’s labor.

Sharing the vision for a more inclusive and expansive social movement, Sojourner Truth passed the baton to Alice Walker who coined the term “Womanism” in her 1983 book “In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens: Womanist Prose.” She described mainstream feminism as a movement led by white women to serve white women's goals and can often be indifferent to, or even in opposition to the needs of Black women.

In contrast, womanism, although inclusive of feminism, is fundamentally dedicated to the history and experiences of Black women. Womanism directly deals with the reality that Black women face both racialized and gendered oppression, and posits that solving for one cannot exclude solving for the other. Walker’s vision also included a queer lens, where the connection to and the love of women go beyond labels of sexual orientation.

“The erotic is a resource within each of us that lies in a deeply female and spiritual plane, firmly rooted in the power of our unexpressed or unrecognized feeling.” – Audre Lorde

As a contemporary of Alice Walker, the work of queer writer and poet Audre Lorde deeply engaged the complex inner worlds of Black women as both a personal and political project.

She believed that due to stereotypes like the desexualized mammy or the hypersexualized jezebel, mainstream feminism’s efforts around sexual liberation and the right to choose could not adequately address Black women’s complicated experiences around sensuality, sexual agency, and reproductive freedom.

Lorde’s work welcomed Black women back into their bodies. Instead of rendering Black women as sexual objects, in her 1978 essay, “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” Lorde encouraged her sisters to see themselves as sensual subjects able to access their instincts as a source of feminine information, joy, and power.

This reclamation of bodily autonomy and self-perception empowered Black women to reject society’s insistence that their expressions of self were shameful. Instead, these words celebrated the wholeness of their being and the power of their embodied femininity.

“We must begin to tell Black women's stories because, without them, we cannot tell the story of Black men, white men, white women, or anyone else in this country.” – Kimberle Crenshaw

The fact is that a truthful, expansive, and grounded understanding of Black women’s humanity benefits everyone.

Celebrated intellectual and political writer Kimberle Crenshaw’s work on intersectionality stands on the shoulders of Sojourner Truth, Alice Walker, Audre Lorde, and countless other ancestors in centering the freedom of Black women in any pursuit of justice.

Crenshaw expounded that there is no oppressive force under which Black women do not carry the heaviest burden. Yet paradoxically, mainstream social movements — whether dealing with issues of gender, queerness, or race — have consistently asked Black women to wait for their time.

That time is now.

When Black women are seen, respected, and held as full humans with all the complexities and multiplicities therein, all peoples are afforded greater access to their truest selves. As we celebrate Women’s History Month, we stand in the long canon of Black women who have refused to let the world define us, and instead dig the deep wells of freedom, self-love, and justice from which all can drink.